Creating the optimal coffee blend

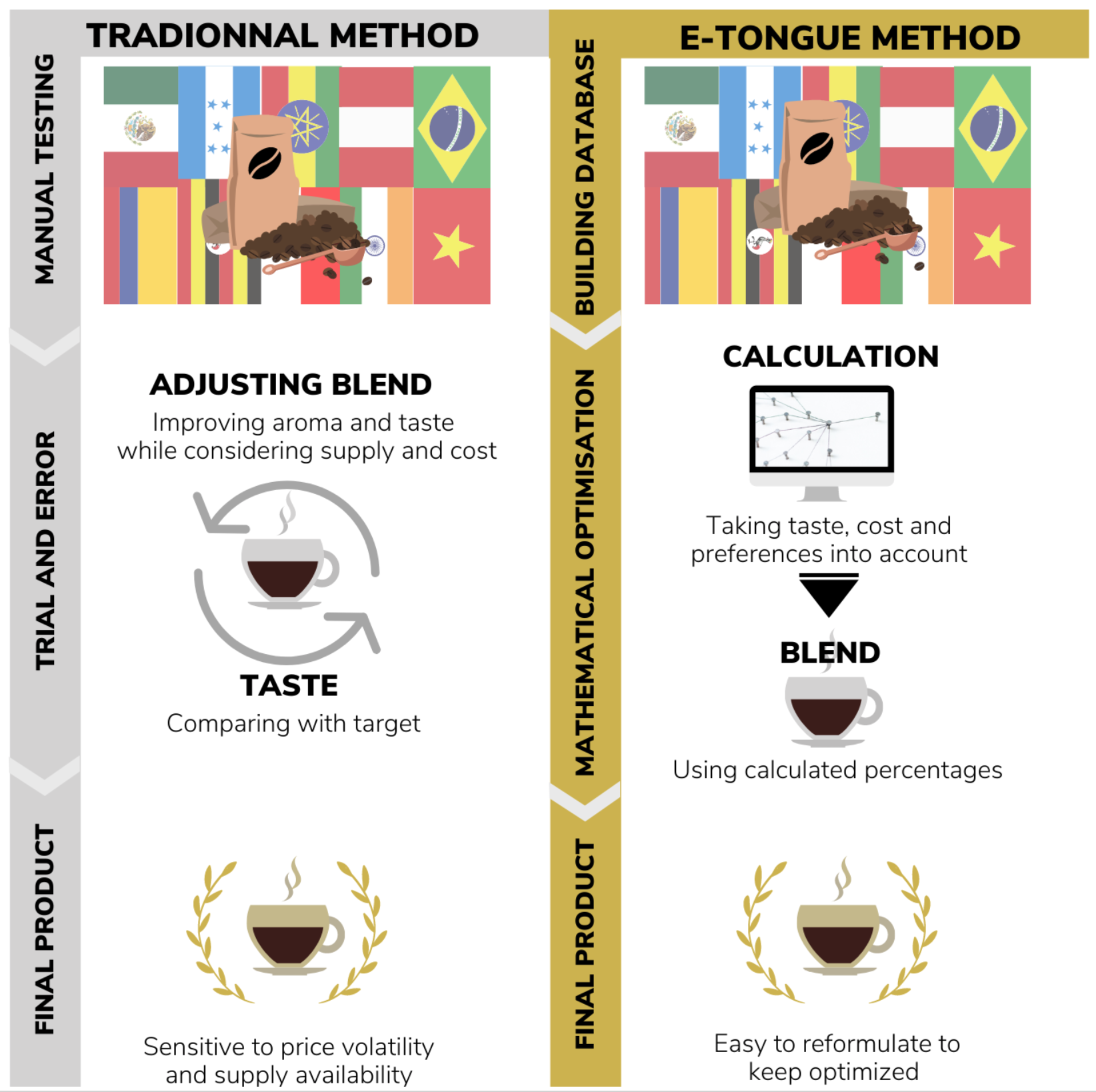

There are only limited places in the world where coffee beans can be grown. Within each, the coffee varieties, growing conditions, and post-processing complexity can greatly differ. This results in a wide variety of coffee quality, taste, and aromatic profile but also, of retail costs. A high cost is often associated with high quality. But do you necessarily need to pay the price to get the best possible taste? From the producer to the roaster, there are virtually unlimited ways to modify the bean’s potential to get a coffee with a unique flavour. An extra layer of complexity comes with the blending of coffee beans. Only the right selection of beans blended in the right proportion can produce the taste you or your consumer desire. At first sight, dealing with this level of complexity to deliver the right formulation can only be achieved by a few experts. Yet, a taste sensing device, also known as the electronic tongue, can help. There are really only two steps to achieve a blend with the taste you want while optimizing cost of the formula:

Measure the taste of all the initial coffee you could use for your formulation using the electronic tongue. This turns their taste into a reliable database, where you could add cost information.

Exploit the electronic tongue software and a mathematical optimization software to work out the percentages for the perfect blend. Taste the result and, in case it might be required, do small adjustments.

That’s it. In this article, we will detail how to do this in more detail, how to exploit this technology to help create the perfect blend.

A look at single blend offerings

To avoid confusion in terminologies, it is worth reminding the difference between taste, flavor, and aroma. The aroma and the taste are two components of flavor. The aroma is perceived both when smelling food or beverage and by retronasal perception. This ones occurs when volatile chemicals are liberated upon consumption. They flow from the mouth through the back of the throat until reaching the nasal cavity where they are sensed. For the perception of the five tastes, direct contact between the tongue and the taste active molecules is required. For complex products such as coffee, both have a great contribution to the tasting experience and are responsible for flavor diversity.

The coffee we all know belongs, in the botanical classification, to the genus Coffea, which is represented by more than 100 species. Within this group, there are only two species that are commercially exploited, grown in most countries between the Tropic of Cancer and the Tropic of Capricorn. The arabica (Coffea arabica) is the most used and makes up 65 to 70% of global coffee production. Secondly comes the robusta (Coffea canephora), produced for its greatest part in Vietnam. Those species are then subdivided into many varieties. Each of them can be produced with a range of specific horticultural or agricultural techniques, giving as many cultivars. Most specialty coffees are different coffee cultivars [1,2] with their singularities. For example, the taste of a Kenyan coffee demonstrates a prominent sourness while an Ethiopian is much more neutral. There is a myriad of environments where coffee is grown around the world. The geographical origins, climate, altitude, and temperature elevation, shading, and the use of fertilizers are environmental factors all suggested having an impact on coffee bean quality [3]. Roasting techniques and other post-treatment also multiply the number of conditions a coffee bean can go through. This is how rare and unique coffees can reach incredible fame, quality, and a certain level of luxury. The black ivory coffee company sells his beans for just over £1600 a kilo. Digested by elephants before being handpicked, carefully sorted, cleaned, and roasted makes it unique. But, it is also the most expensive coffee in the world. Other famous (and more reasonably priced) coffees are for example the Saint Helena coffee, Jamaican Blue Montain coffee, Finca El Injerto Coffee, Los Planes Coffee retail between £50 and £80/kg. Not everyone might be ready to make such investment in their daily brew.

Turning coffees from around the world into a taste database

This is when the electronic tongue can come into play. It is its core uses and also where it performs the best. The e-tongue can take actual samples, repeatedly measure and evaluate their taste profile until turning those sensory properties into quantified values. If you have 100 different coffees you want to test, describe, and classify, how would you proceed? Doing it by hand is a very tedious task that will take weeks if not months to complete. And even there, how much can you trust the information you have collected? How many people will have to repeat the same process and how many times to make it unarguable? The machine won’t get tired or won’t have its senses saturated. If we take the TS-5000Z made by the Japanese company Insent that we use at New Food Innovation, it can analyze the taste of up to 20samples a day. Even with a fair number of repetitions, it makes possible the obtention of reliable data from a large number of samples, in a limited time. Once available in the form of a database, it simplifies the computations. It offers the possibility to virtually blend coffees and to predict the results without the need for actual experiments.

Mathematical optimization for creating the perfect blend

How do you use this data? Taste doesn’t simply add one with the other. If you manage to determine that a brewed coffee presents half of the bitterness you want to achieve, doubling the quantity won’t do the trick. The proportionality isn't there. This was initially demonstrated in the 40s with studies on taste grounding themselves on the Weber and Fechner law [4]. For all tastes, a change of 20% in the concentration of the taste active molecules between two samples is the minimum required to feel any change. If there is already one sugar in your coffee and it is not quite sweet enough, you need to add at least 0.2 extra sugar to make it sweeter. Anything lower than that is too small and won’t be noticed. If you want to double the taste intensity you shouldn't double the quantity but multiply it by roughly 4 (resolving (1.2)nTi = 2Ti, where Ti is the initial taste value). Based on this logarithmic increase, Insent developed its taste scale. A change of one unit on the scale translates a perceivable difference. Once the artificial “brain” has received the crude data, it has the ability to convert them on this scale. Mathematical manipulations are now easy and become a matter of working out the right percentages. If we have the data available of m different coffees, the equation to solve becomes:

Tasten (blend)=%1× Tasten (Coffee1)+%2×Tasten (Coffee2)+⋯%m×Tasten(Coffeem)

Where Tastenareto select between the different tastes measured depending on the objectives : Sweetness, saltiness, sourness, bitterness, astringency, umami and their respective aftertastes. Any data on cost or additional information can be added easily to the mix. With the appropriate equation resolution software, the different percentages of the coffees available can be worked out to create the blend with the taste you want. The only remaining step will be to go straight to the final blend. There might be some small final adjustments required. Yet, those are almost meaningless compared with the effort required to achieve the same result manually.

This is very theoretical. Let’s give a real application example. With the information gathered from 4 coffee origins, the software found a blend giving a taste profile very close to the one targeted.

This strategy has been used, for instance, by the company Ishimitsu Co., Ltd., a long-established Japanese coffee manufacturer in Japan. Through mathematical optimization of the taste, they developed a product that tastes just like the market leader. There is however a strong differentiating point. The choice of the beans to use was carefully done based on their taste profile, but also their cost. The consequence? The use of the e-tongue made possible the formulation of a product that not only has a similar taste than the competitor but also a 10-20% cheaper raw material cost. Taste sensors are thus proved to be a powerful tool for coffee blending. An electronic tongue can optimize not only the taste but also the price in a much easier and less labor-intensive workflow. In comparison, a human blender can make on-target taste only if he or she is well-trained.

Other uses of computer-assisted formulations

The obtention of the ideal combination of taste and price is achievable. What other areas can be explored based on the same database? You can input any information of interest to be part of the data and best optimize for this new input and taste simultaneously. The taste sensor can provide an objective gauge for the taste of coffee, which can give appreciable effects on the coffee industry. Some applications are for example the elaboration of a taste map, the use of data to train future professionals or the rationalization of beans storage. There are actually a lot more than that. Yet, these examples may provide ideas on how to best exploit e-tongue technology for the coffee industry.

Elaboration of taste maps for better market insights

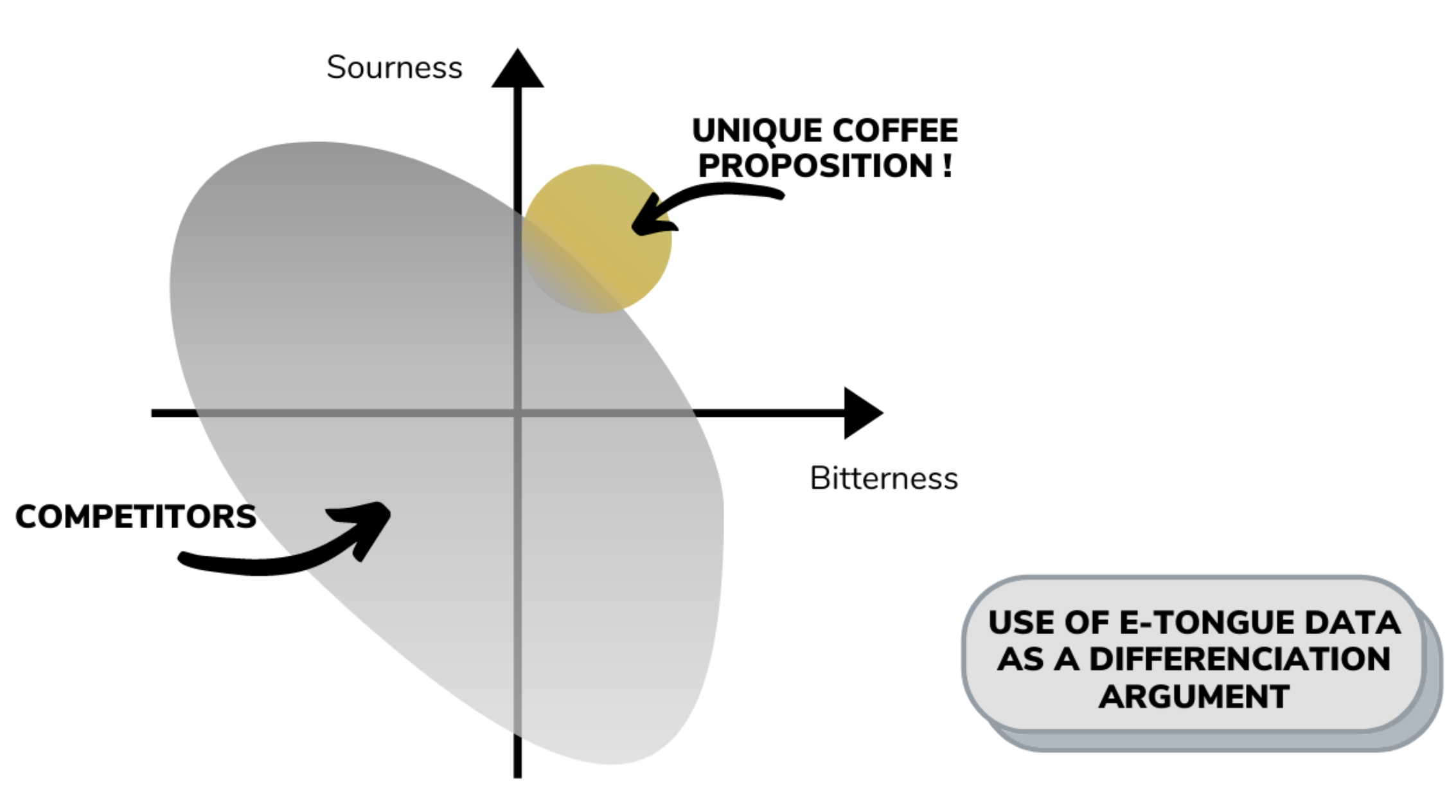

With a straightforward use of the data, you can pick the tastes that are most relevant to you and draw a projection of the data on a graph. The generation of what is called a taste map is made simple. A first use of such a map is to show to consumers an accurate representation of the taste of the different products of a range. Another angle can also be to visualize how your product positions itself against the competitors. A good understanding of the product qualities is the first step to analyze what the consumer desires and ultimately, what he is the most likely to buy. Taking the opposite view, you could also prove how different your coffee is from the rest of the market. If this represents a market opportunity, the design of a coffee that, in purpose, offers a new value proposition to the market is achievable. The elaboration of a marketing operation based on trustable data can be conducted. This following graph illustrates this ease of representation.

The facilitated acquisition and increased accumulation of data lead to a better understanding of the client. This can result in fast, accurate, and efficient product development or advantageous strategic positioning.

The facilitated acquisition and increased accumulation of data lead to a better understanding of the client. This can result in fast, accurate, and efficient product development or advantageous strategic positioning.

Simplify training of new professionals

Educating and training senses is a lengthy task. Developing taste expertise relies on five principles: more repetition; more refined, complete, and veridical cognitive structures; more ability to analyze information; more ability to elaborate on information and more ability to remember [5]. The initial training bases itself on education. Novice will need to try a lot of samples with the supervision of an expert teaching how to pick the different subtleties of the coffee flavor. The electronic tongue can be used to measure a variety of samples and their associated taste representations. Inexperienced professionals can use this guide to develop their expertise with little supervision. The same principles can be applied to empower coffee drinkers. It opens an opportunity to give them the tools to better grasp the differences in the offering and put more accurate descriptions of their likings.

Simplify logistic and storage with a better beans management

A coffee blend uses in general 2 to 5 different types of beans. It is recommended that none of the beans represent less than 8% of the total blend, as it makes it too dilute and increases the risk of it not being part of the final blend. Each blend is unique and has its own taste profile. If the objective is to offer a range of different coffee blends, the number of raw ingredients increases drastically. Ensuring the supply in adequate quantities to cope with storage issues while keeping an eye on market price changes is a challenge. The difficulty of this challenge is even enhanced when increasing the number of beans to deal with. By using a taste database gathered using the electronic tongue, rationalization is facilitated. Starting with the taste data of all the single blends stored and the ones of the final blends already designed, you can discover overlaps. The use of a taste database enables the identification of bean substitutions and blends simplifications, ultimately leading to a more straightforward logistic.

Turning tastes into data is what the electronic tongue is designed for. Exploiting taste data can then be used to improve performances, trigger innovation, reduce cost, and give a better understanding of the market. With the right support and exploitation strategy, the electronic tongue can be a valuable asset for a coffee company or any other industry where taste matters.

Florian Woisel

Sources:

[1] Speciality coffee association of America, http://scaa.org/index.php?goto=&page=resources&d=a-botanists-guide-to-specialty-coffee, accessed on the 8th of July 2020

[2] Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, https://www.kew.org/plants/arabica-coffee, accessed on the 8th of July 2020

[3] Sunarharum, W. B., Williams, D. J., & Smyth, H. E. (2014). Complexity of coffee flavor: A compositional and sensory perspective. Food Research International, 62, 315-325.

[4] Lewis, D. R. (1948). Psychological scales of taste. The Journal of psychology, 26(2), 437-446.

[5] Alba, J. W., & Hutchinson, J. W. (1987). Dimensions of consumer expertise. Journal of consumer research, 13(4), 411-454.

Other notable source : Toko, K. (Ed.). (2013). Biochemical sensors: mimicking gustatory and olfactory senses. CRC Press.